Introduction – Shrink Your Service Footprint

Even if you spend a lot on services their emissions won’t dominate your footprint. In fact, if by spending more money on services you spend less in other areas you should reduce your total personal footprint.

In this step we will look at what a service footprint is, the carbon intensity of services, buying fewer services, buying more services and low-carbon services.

Service Footprints Defined As Footprint From Services Purchased

A person’s service footprint is the sum of the all the footprints from each service they purchase. Although service footprints can also be quite complicated they are often made up of a few major components than product footprints, making them simpler to assess.

Services we commonly use like health care, education, hospitality and finance share many things in common. The wages of staff make up a significant share of costs but have a limited footprint. They use an office or place of work which requires electricity, heating and sometimes cooling. Staff need to travel, equipment is procured and waste is generated. Together these sources of emissions make up a service’s footprint.

IO-LCA Is Used To Analyze Service Footprints

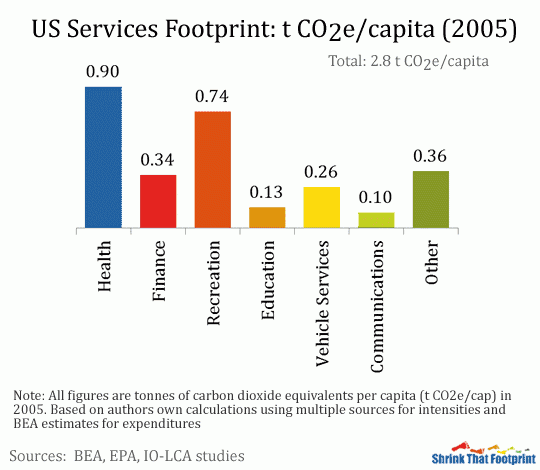

As with products we can use Input Output Life Cycle Assessment (IO-LCA) to analyse a typical American’s service footprint. For simplicities sake we split service expenditure up into seven different groups. These are health, finance, recreation, education, vehicle services, communications and other. Using weighed average intensities from different US studies we estimate our footprint by multiplying the expenditures in each group by the intensity.

Our estimate looks like this:

In total the average US services footprint comes to around 2.8 t CO2e per person. This is dominated by health care and recreational activities with the rest quite well spread across finance, education, vehicle services, communications and other services. The major components of each groups are listed below:

Health: Doctors, dentists, hospitals, paramedics, nursing homes

Finance: banks, accountants, net insurance, investment

Recreation: memberships, sports, culture, hotels, restaurants, gambling

Education: nursery, primary, secondary, university, tutoring

Vehicle: service, repair, cleaning

Communications: telephone, internet, postal

Others: professional, household, personal care, clothing, religious

Because these services are aggregated into groups we can’t say much about specific services. All figures are based on private expenditures so they do not include services paid for indirectly through taxes like public health, public education, policing and the military.

Together health and recreation make up almost three fifths of the total footprint. This is largely a result of the amount of money people spend on these services, rather than them being more carbon intensive than other services.

The Carbon Intensity Of Services

For this US footprint example we have used estimates based on IO-LCA literature. This method gives us a rough idea of the carbon intensity of spending in each of our seven groups.

The carbon intensities for each group range from 0.14 kg CO2e/$ in finance to 0.37 kg CO2e/$ in vehicle services. The weighted average across all services is around 0.2 kg CO2e/$. Meaning that on average for each $5 spent around a kilo of CO2e is produced.

As a general rule services that involved a lot of procurement, like vehicle services and recreation, tend to be more carbon intensive because the spending includes a large share towards product purchasing. The likes of finance and communications services are less carbon intensive because they include a large share of cost spent on wages.

A very detailed IO-LCA model could give information much more specific than this example, often having as many as a hundred different service sectors. But even with such detail these estimates rely on the assumption that your service provider is typical of the national average, which may or may not be the case.

An alternative to IO-LCA is if a service provider does a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for a service or more commonly their entire business. Such studies produce a detailed footprint for a business which is typically split up in to areas like office energy, travel, procurement and waste. Taking a business’s footprint and dividing by annual revenue provides a good estimate of how carbon intensive any service that business provides is. For the business itself the LCA study provides a baseline for any plans to reduce this footprint.

When thinking about your own service footprint it is important to remain aware of your whole footprint and how purchasing services may affect this. In each of the categories we have looked at so far reducing your footprint means either doing something less or doing it less carbon intensively. While the same is true of services, switching spending from other categories to services is also a carbon reduction strategy.

Buying Fewer Services Is Not Always Good

Buying fewer services will reduce your service footprint, but it isn’t always desirable or sensible. Health and education services are necessities while many financial, vehicle and communication services are also things we use on a day-to-day basis. And though recreational and other services may be less necessary, they tend to be things that are quite enjoyable.

Although reducing your service spending might be difficult you may well find plenty of areas that you would happily spend less on. The most obvious is debt. Most of us would gladly pay less for mortgages, loans and particularly credit cards, though this is easier said than done. Much the same can be said of phone bills, Internet, television costs and many other subscription services where costs can easily get out of control.

If you are conscientiously reducing your footprint in all areas, then services will just be another sector in which you focus on either buying less, or finding lower carbon options. But because most of us live on a budget if we save some money in one way we often spend it in another. If you were to save some money on your phone bill, gym membership or insurance, and then spend it on a new computer or a plane flight, then that shift in expenditure would actually increase your footprint. In this contexts spending more money on services could help to reduce your personal footprint, even if it did increases your service footprint.

Buying More Services For Housing, Travel, Food Or Products Is Mostly Good

Can you simply buy more services to shrink your personal footprint? If by spending more on services you reduce your spending on housing, travel, food or products, then the answer is probably yes. This is due to the lower carbon intensity of spending on services compared to other categories.

To explain this idea more clearly we can use data from each of our five main categories. For each category we take the typical footprint per capita and divide by average expenditure in that category. This results in an average carbon intensity for spending within each category.

Spending on housing is hugely carbon intensive at 6 kg CO2e/$, travel spending (2.5 kg) is quite intensive and food expenditure (1.0 kg) is moderately so. Product spending (0.5 kg) has relatively low intensity and services (0.2 kg) are by far the least carbon intensive way to spend. While these averages mask individual variation within each category the differences between sectors is stark.

For a practical example let’s say an American switched $100 of typical spending away from each other category to services. Switching $100 from housing would have reduced their footprint by 580 kg, from travel that reduction is 230 kg, from food it is 80 kg and from products it would be 30 kg. Given that average US spending per capita on things other than services was more than $12,000 in 2005, the potential for switching spending to services as a carbon reduction strategy is very large.

As a general rule targeting reductions in a few carbon intensive forms of spending is a simple and effective way of shrinking your personal footprint. Although we won’t go in to many specific examples, two in particular are worth mentioning, petrol (gasoline) and electricity.

Despite spending less than $500 on electricity and $1000 on petrol in 2005, the average American had footprints of more than 3 t CO2e for electricity and 5 t CO2e for petrol (gasoline). Combined, these footprints amount to more than 40% of the average personal footprint despite accounting for less than 6% of a typical American’s spending.

In 2005 the carbon intensity of electricity was 7.3 kg CO2e/$, while for petrol it was 5.3 kg CO2e/$. Moving just $100 from each of these and spending it on an average service would have resulted in a 710 kg reduction for the shift away from electricity, and a 510 kg reduction for the shift from petrol.

So are such shifts realistic? To a degree they are, perhaps more than we might think. Although people generally choose to spend the way they do because of their preferences, a lot of spending is as much a force of habit as anything else. Many spending shifts can be relatively painless and sometimes actually quite positive.

Shifting some spending from your heating bill to buying insulation could be good for both you bank balance and footprint, particularly in the longer run. Having a more fuel efficient car can shift spending away from petrol to other less carbon intensive things, like going to the restaurant or cinema more often.

The relatively low-carbon intensity of services and high number that are necessities means that services are probably the last area of your footprint you should prioritise when looking for reductions. Instead focusing on areas where your spending is more carbon intensive will be much more fruitful, even if that results in a slightly bigger service footprint.

Low Carbon Services Enhance Gains

Although services are relatively low-carbon to begin with their footprints can still be improved. Unlike with other categories the footprints of different services are often quite similar. They share the need for a work space, electricity, heating, cooling, travel, equipment, products and support services.

The major sources of emissions are electricity and procurement, which includes all equipment, products and support services. Natural gas and travel are also significant, while waste makes up a small share. Although these figures are averages, they give us a decent idea of what a typical service might look like.

In most cases it is quite difficult to calculate how carbon intensive a service you buy is, other than by assuming it is similar to national estimates for that type of business (if those estimates exist). This is slowly beginning to change. More and more companies are assessing their corporate footprint and releasing those assessments to the public.

Although consumers can use this information to compare the services they buy, the major value of this information is to help the business direct its carbon reduction strategy. Reducing the footprint of a service company is much like shrinking a personal footprint, but on a much larger scale. To do so you a business must look at the major components of a service footprint: energy use, travel and procurement.

Energy use: Reducing emissions from an office involves the same two pronged approach as in the home, reducing energy demand and using lower carbon energy. This involves reducing electricity used by lights, computers, computer servers and appliances, particularly when they are not being utilised. To reduce heating and cooling needs you can improve the insulation and air tightness of the building envelope. Having reduced energy demand businesses can also source lower carbon electricity or invest in a low-carbon heating systems.

Travel: Travel emissions are much the same for businesses as for individuals, so lowering emissions means either less travel or lower carbon travel. Relying more on teleconferencing and being more selective about destinations can reduce the distances travelled. Using low-carbon vehicles for company cars can also impact travel footprints significantly, as can increased use of public transport. Practical alternatives to flying remain limited.

Procurement: As with our own products footprint, understanding and reducing a procurement footprint can be challenging. Reducing unnecessary and wasteful purchases is a potentially useful strategy. Reuse of products and second hand purchases may be less practical in the corporate world, but could still be of value in the right context. Perhaps the options with the most potential is sourcing products with low-carbon design and improving corporate recycling.

The large parallels between service and personal footprints are important. By learning about and trying to reduce their own footprints people are much better equipped to understand the business footprint of the place they work. Increased understanding of carbon footprints among employees, and executives in particular, can dramatically improves a business’s ability to shrink its corporate footprint.

Summary

In this step we looked at how our service footprint is a combination of footprints of each service we pay for.

We analysed the average US services footprint and showed how the carbon intensities of many services are in fact quite similar. We explored how buying fewer services can reduce our service footprint, but also how spending more on services may help to reduce our personal footprint as a whole. Finally we showed how the similarities between personal and service footprints mean that many lessons are transferable from the home to the boardroom.

In the next step we look at taking further climate action.

Back To The 30 Day Shrink Guide: Introducing the Shrink

Lindsay Wilson

I founded Shrink That Footprint in November 2012, after a long period of research. For many years I have calculated, studied and worked with carbon footprints, and Shrink That Footprint is that interest come to life.

I have an Economics degree from UCL, have previously worked as an energy efficiency analyst at BNEF and continue to work as a strategy consultant at Maneas. I have consulted to numerous clients in energy and finance, as well as the World Economic Forum.

When I’m not crunching carbon footprints you’ll often find me helping my two year old son tend to the tomatoes, salad and peppers growing in our upcycled greenhouse.