Sales Of Tablet Computers Forecasted 134 Million In 2022

Tablet sales peaked in 2014 at the height of their popularity. Since then, laptops have made a slow comeback so that this year its projected laptops will see sales of 165 million units world-wide whereas tablets only 134 million. Nevertheless, that’s still a hefty amount! If you unwrapped a tablet computer on Christmas day then you’re in luck. Not just because someone you know has deep pockets, but because it could help to reduce your carbon footprint in more ways than one.

This post gives four reasons why the tablet computes are surprisingly good for the planet.

1: Production Footprint

Although tablet computers are sometimes derided as not replacing anything, or an unnecessary use of resources, when judged by carbon emissions they actually stand up very well to other computers.

As part of a campaign to stress their eco credentials Apple publish a life cycle analysis for each new product. These Product Environmental Reports give a snapshot into the emissions created during the different phases of each product’s lifecycle. These phases are materials, manufacturing, distribution, customer use and recycling.

To help us understand the carbon footprint that arises from producing a computer we will compare six different Apple products:

- iPad mini (tablet): 64 GB wifi + cellular ($659)

- iPad 4 (tablet): 64 GB wifi + cellular ($829)

- MacBook Air (laptop): 13″ 128 GB ($1,199)

- MacBook Pro (laptop): 15″ 500GB ($1,799)

- iMac (desktop): 27″ 1TB ($1,799)

- Mac Pro (destop): 27″ Thunderbolt dispaly, 1TB ($3,499)

By comparing these different models we will get a look at the type of carbon footprint different forms of computing generate. Although not exactly comparable to other brands, this gives us an insight into the emissions difference between tablets, laptops and desktops.

In order to get a snapshot of each footprint we will compare the sum of the material, manufacturing, distribution and recycling emissions. This will be our ‘production footprint’. Customer use emissions are omitted because they differ greatly depending on the amount of product use and the source of the electricity.

It is pretty clear that as computers get bigger, so does their production footprint.

Starting from the iPad mini with its small 74 kg CO2e production footprint through to the Mac Pro which weighs in at more than a tonne, footprint size increases with physical size. This is both a function of needing more materials and the fact that specifications tend to improve with size.

What we can’t see here is the fact that materials and manufacturing are responsible for about 90% of each footprint. This is not surprising as the manufacture of processors, memory and displays are all very energy intensive. For laptop computers like the MacBook Air and Pro, the battery manufacturing can also have a significant footprint.

If it’s a small production footprint you’re after, the iPad mini is the winner by some distance.

Note: this analysis focuses purely on carbon emissions. It does not consider further issues of sustainability within the supply chain.

2: Power Footprint

Compared to larger Apple computers the iPad mini uses just a trickle of power.

Although the Apple reports do include estimates of ‘customer use’ footprints these assume different usage patterns and carbon intensities for electricity that have changed over time. In order to do a ‘like-for-like’ comparison we will instead compare the power footprint of having each computer on for 10,000 hours using an average mix of US electricity. 10,000 hours is a rough estimate for lifetime usage.

The difference in the power footprint between each of the six models is pretty astounding, but typical of the divides between tablets, laptops and desktop computers.

The iPad mini again leads the way with just 16 kg CO2e resulting from its power use over 10,000 hours. Compared to the iPad mini the iPad 4 has twice the power footprint, the MacBook Air four times and MacBook Pro about 7 times. Nonetheless these footprints are all small compared to desktop models. This is natural as to maximize battery life great attention is given to improving energy efficiency mobile computing.

The difference between these power footprints comes down to their power use (wattage). For the iPad mini the wattage of idling with the screen on is just 2W, which is similar to other small tablets like the Nexus 7 or Kindle Fire. This compares to 15W for the MacBook Pro and 250W for Mac Pro with Thunderbolt display.

The scale of these differences is broadly comparable to most ranges of tablet, laptop and desktop computer. You can exploit the superior energy efficiency of tablet computers by switching away from desktops and laptops when possible.

Note: this analysis assumes typical US grid electricity based on data from 2009. This includes emissions from fuel combustion, fuel production and grid losses. As a result emissions will vary for places with lower or higher carbon electricity than the US average.

3: Media Footprint

Small tablet computers also have the potential to reduce your media footprint, depending on how you use them.

Other forms of media have their own footprints which a tablet computer can potentially help to reduce. This might be by avoiding the production of newspapers and books, or by reducing the time you spend watching TV, playing a games console or using a desktop computer. Each of which use considerably more electricity. This is ironically even true for eco-friendly books which are written to spread knowledge of reducing waste and increasing sustainability.

The opposite argument could also be made. That tablets don’t really replace anything in particular, and that they simply add to the pile of gadgets and stuff that continues to grow. This is exemplified by people using tablets whilst watching TV.

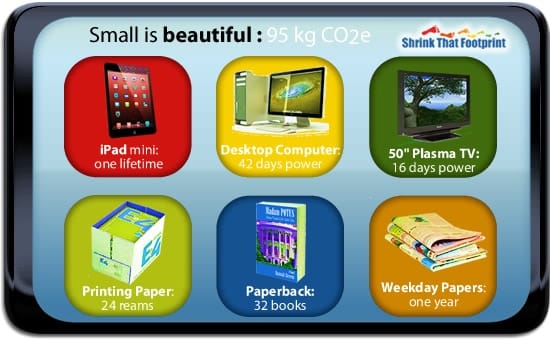

We can throw some light on these arguments by comparing the lifecycle emissions of the iPad mini to other forms of media. For this example we will use the official Apple estimate of 95 kg CO2e for its lifetime footprint. This is composed of 66 kg for materials and manufacturing, 6 kg for distribution, 21 kg use (4 kg more than our 10,000 hour estimate) and 2 kg recycling.

To compare this to books, printing paper and newspapers we will estimate production footprints for each. Comparing to computer, TV and games console use we estimate a power footprint. For each we work out the footprint of a functional unit, like for a book or a day’s power use (24 hours), then divide the 95 kg by that footprint to estimate how it compares.

iPad Mini Lifetime Footprint Of 95 kg CO2e Equivalencies

Based on our rough estimates it equates to any of the following: 12 hardbacks, 16 days of non stop plasma TV, 24 reams of paper, 32 paperbacks, 40 days of gaming, 42 days of desktop computer use, 64 days of a LCD TV, 106 Sunday papers,and 237 weekday papers.

With these numbers we can estimate when an iPad mini might start reducing someone’s media footprint. For example if you ditch your weekday paper subscription and read it digitally you’ll break even after about a year, for the Sunday paper alone its two years. For hardback books the breakeven is 12 books, while for paperbacks it is 32.

If your iPad causes you to watch 675 hours (16 days) less plasma TV you’ll be in the black, in terms of carbon that is. For gaming it is 950 hours (40 days) and for a desktop about 1020 hours (42 days).

In reality the impact of owning a tablet computer will probably be a combination of effects. If it causes a large reduction in your purchasing of physical books and newspapers it is probably good for your media footprint. Likewise if it significantly reduces your use of high wattage devices like plasma TVs, desktop computers or games consoles it is also likely to have a positive effect.

Note: this analysis assumes typical US grid electricity and paper manufacturing. In countries, or states, with lower carbon electricity the paybacks would be slower. In places with more carbon intensive electricity it would be faster. The footprints of books and newspapers are sensitive both to their weight and share of recycled paper, so these figures should be considered rough estimates. Server emissions are omitted from this analysis due to them not materially affecting the results on a per download basis, but significant use of cloud storage would alter this.

4: Consumption Footprint

If you buy an iPad mini, and never turn it on, it’s probably still good for the planet.

That sounds a little crazy, but consumption based footprinting analysis shows this to be the case.

Each two dollars that is spent in the US economy typically causes one kilo of carbon dioxide equivalents to be emitted. In other words the carbon intensity of spending in the US economy is about 0.5 kg CO2e/$. This figure is a consumption based footprint that is adjusted for imports and exports.

The iPad mini that Apple report on has a retail price of $659 and a production footprint of 74 kg CO2e. Dividing the footprint by price we see that this top of the range iPad mini has a carbon intensity for spending of just 0.11 kg CO2e/$, which is very lean. In fact all six products compared here range between the iPad mini and the Mac Pro at 0.3 kg CO2e/$, due in part to the premium pricing on Apple products. This seems about right given that Apple Inc. report an average of 0.22 kg CO2e/$ for each dollar of revenue.

So, for the full specification iPad mini the carbon intensity of spending is around 0.11 kg CO2e/$, or a quarter of the national average. That is impressive, but only by comparing to some other carbon intensities can you see just how good it is.

The following charts compares the average carbon intensity of spending on different things in the US economy.

Although the iPad mini looks good next to the average of 0.49 kg CO2e/$, it looks very good when compared to spending on things like electricity, natural gas and gasoline.

In fact such low carbon intensity is generally reserved for services which require limited energy inputs like gardening, cleaning or hairdressing.

To make this point clearer we can use these intensities to estimate the consumption footprint of spending $659 elsewhere in the US economy.

Convinced Yet?

It turns out a full specification iPad mini is an incredibly low carbon way to spend $659, generating less than 100 kg CO2e as result.

If you were to spend that $659 elsewhere you could probably only do better by paying for low carbon services or a project that is designed to reduce emissions.

If you spent that $659 on average stuff it would be 300 kg CO2e or 700 kg on food. If you used that $659 to fill your tank it would cause almost two tonnes of emissions. And if you spent it at home on natural gas or electricity it would create a whopping 3,400 kg CO2e footprint.

Most people live on a budget. Which means that if they spend money on one thing they have to cut back on others. So if someone spends $659 on an iPad mini, the chances are it would have created a bigger footprint being spent elsewhere.

Note: each consumption based footprint in this section is a broad average for that type of product or service. As such individual product or service footprints may vary considerably from these averages

Time To Buy A Tablet?

Although this analysis has focused on the iPad mini, each of these four reasons is likely to apply to tablet computer, particularly small ones.

They can be summarised as follows:

1) Production Footprint: If by buying a tablet you buy less frequent laptop or desktop computers, it will probably reduce the production footprint of your computers in total.

2) Power Footprint: Using a tablet instead of a laptop, or better yet a desktop, will reduce both your power footprint and your electricity bill.

3) Media Footprint: If you use a tablet as a substitute for physical books and newspapers, or instead of a TV or games console, it will probably improve your media footprint.4) Consumption Footprint: Small tablets, and the iPad mini in particular, are a relatively climate friendly way to spend money. If you save for one by reducing your spending on gasoline, natural gas or grid electricity, you could reduce you own carbon footprint by more than one tonne.

Lindsay Wilson

I founded Shrink That Footprint in November 2012, after a long period of research. For many years I have calculated, studied and worked with carbon footprints, and Shrink That Footprint is that interest come to life.

I have an Economics degree from UCL, have previously worked as an energy efficiency analyst at BNEF and continue to work as a strategy consultant at Maneas. I have consulted to numerous clients in energy and finance, as well as the World Economic Forum.

When I’m not crunching carbon footprints you’ll often find me helping my two year old son tend to the tomatoes, salad and peppers growing in our upcycled greenhouse.