One of the nice things about not blogging over the holiday period has been the chance to catch up on other blogs. Llyod Alter’s December pieces in particular have been fascinating, his year in urbanism roundup a real highlight.

Another thoughtful piece was an invitation to discuss the question “Are electric cars going to make it harder to fix our cities?” In it he again posits that the problem with American cars is ‘not under the hood’ and questions whether electric cars could help reinforce problematic urban sprawl. Since this question was posed in 2013, it has become more pertinent a full 10 years later in 2023 because both legislation and natural consumer demand has led to incredible adoption of electric vehicles such that they make up .

Zach Shahan took up this discussion by defending the importance of electric cars in a comment and follow up piece. He argued that, like it or not, cars are here to stay for the foreseeable future, so we need to decarbonize them while also making cities less dependent on them.

Like Zach I’ve lived in Holland and being able to compare it to my time in Australia and the UK I’m also quite evangelical about the superiority of green cities which prioritize cycling and walking over cars including those designed to be so compact for city streets that they’re almost not cars like the Renault Twizy concept micro-car.

But if I take my own preferences out of the argument, and look at the data, the reality tells me we need both better cities and better cars, because people still want cars.

As ever I’ll let the data do the talking:

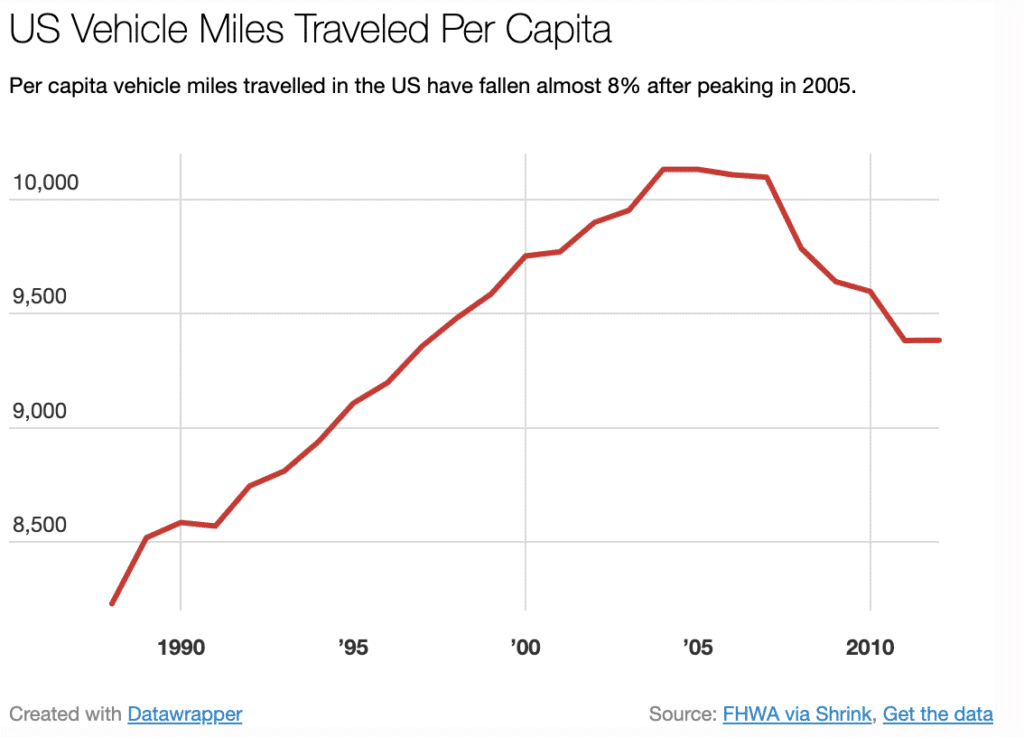

US Driving Has Declined Recently

If you are looking purely at the American experience the argument for a push away from cars is very strong. US car travel peaked in 2007 and vehicle miles travelled per capita fell 8% between 2005 and 2012.

I’ve argued before that high oil prices have played a big role in this, but the most fascinating part of this change for me has been the moving preferences among young Americans.

Over the period 2000-2009 Americans aged 16-34 travelled 23% fewer miles by car, cycled 24% more often, walked 16% more frequently and travelled 40% more miles by public transport . There is a summary in our generation twitter post.

Although this data supports a possible American push-back against the car, looking at the picture globally makes one less sanguine.

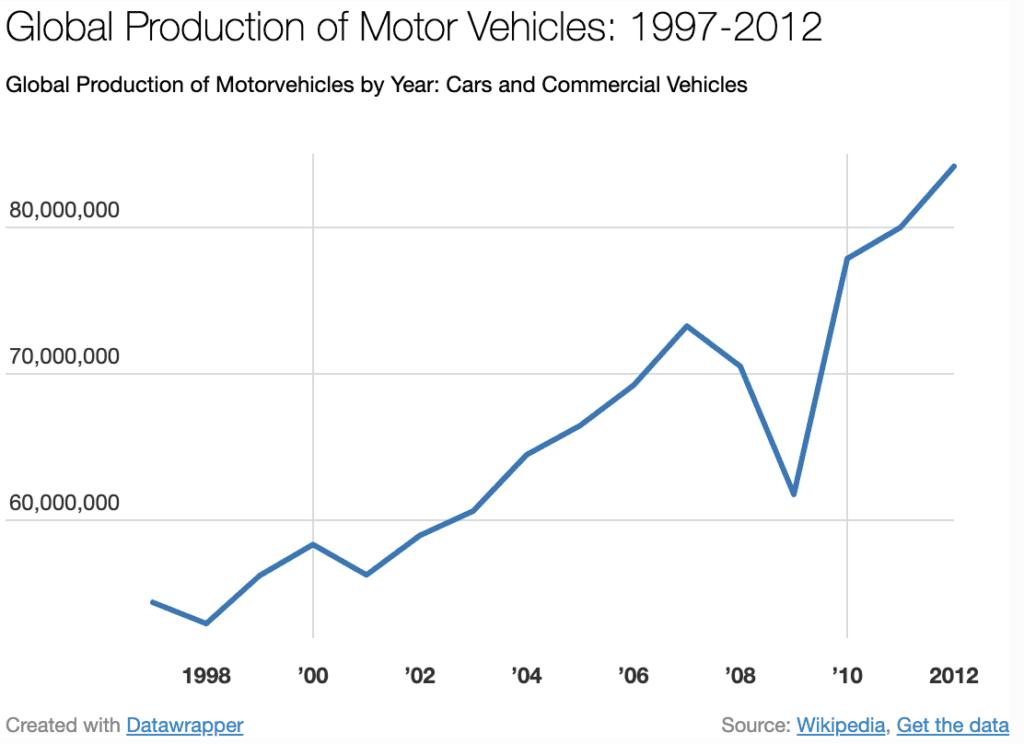

Car Manufacturing Is Still Trending Up

The BBC ran a wonderful Hans Rosling talk/documentary recently about demographics called Don’t Panic. In it he described the transition from extreme poverty to wealth in five stages of transport.

The first was to buy shoes, then a bicycle, followed by motorbike, then a car and finally to be able to afford to fly. Although I’m well versed in how sustainable these different transport modes are, it is hard to escape the reality that the world now has a billion people that currently own a bike, e-bike or motorbike but aspire to own a car. Cars may become less fashionable in time, but I can’t see that in the data today.

Demand from the burgeoning middle classes in places like China, India and Brazil underpins the continuing growth of car manufacturing globally.

In the wake of the global recession in 2008 and 2009 vehicle manufacturing has rebounded to 84 million in 2012. Although I realize that the atmosphere can’t afford all these new cars I wouldn’t bet much on that curve flattening, much less dropping.

Using low carbon power electric car emissions are about a quarter of an inefficient gasoline car and half that of a top hybrid, that includes their considerable construction footprint. If battery prices keep dropping EVs could play a very big role in tackling transport emissions.

I’m still waiting for Toyota to build a full electric, but EVs are looking more competitive by the year. They aren’t a panacea by any stretch, but they are one of many important levers.

America Is The Key EV Market in Terms of Carbon

As much as America can benefit from better, denser cities, it is also the place in the world where electric vehicles could make the biggest emissions difference quickly. There are two reasons for this:

The first is that the carbon benefits of electric cars are extremely dependent on where the electricity comes from. I’ve covered this before in our Electric Car Emissions report, and in the more readable The ‘Electric Cars Aren’t Green Myth’ Debunked.

The basic point is that electric cars are only as good as their juice. When using coal powered electricity like in China, India and Australia electric cars have limited carbon benefit, they simply move the emissions around the supply chain. So although China is by far the biggest new car market, good hybrids are probably a better bet for slowing transport emissions growth there in the short term, alongside the stratospheric growth of electric bikes. EV benefits in China may be greater in tackling local air pollution.

Things are very different in the US. In a great number of US states electric cars have far lower carbon emissions than the best hybrids, plus local air quality benefits. Moreover, the fuel economy of new cars in the US is still very low at 27 MPG, so each EV purchased makes a bigger difference.

The second reason the US is the most important EV market for carbon is that Americans drive more than everyone else. Consider this statistic for a second. In 2010 the total road passenger kilometers travelled in the US were greater than in China, India, Russia, Germany, the UK, Italy, Spain and France combined. The American love affair with the car is truly mind-boggling!

In the visualization below I’ve mapped road passenger kilometres per capita from 2010 with data from the World Bank. It looks a little empty but if you hover over the map you’ll find data for 50 countries. In the top right you can go fullscreen.

In 2010 the average distance travelled by an American on roads was 22,081 passenger kilometres. This was 43% further than a typical Canadian, 60% more than an Australian, double that of a Britian and 20 times more than the Chinese average (remembering most don’t own cars).

Even though Americans are driving less than a few years ago, they still drive a colossal amount. As such EVs have the potential to reduce total driving emissions in the US more than anywhere else, while we wait for Gen Y to go urban.

Better Cities and Cars

Given the continued momentum of global car sales we desperately need low carbon vehicles like EVs. I’m pretty squarely in agreement with Zach on this. Not because I want to be, but simply because that is what the data tells me.

With the current state of electric car technology I’m also not convinced they are doing anything much to increase the total demand for cars, so I’m happy to see them substitute for ones using oil if they use low carbon electricity.

In the longer term I think Lloyd Alter brings up a really interesting point, which he noted in a comment on Cleantechnica:

I remain convinced that once the self-driving electric car becomes the norm (and I do not think that it is that far away) it will be a licence to sprawl

Now I’ve got no clue how close self-driving electric cars, but this point makes sense to me. A half hour commute reading a book for me would be many fold more tolerable than driving the same period of time. Could that facilitate more sprawl? It’s seems possible, and should certainly be on planner’s radars.

In a post a few months ago about the 5 Elements of Sustainable Transport my fifth element was urbanization. That is where I’m in full agreement with Lloyd and part of why I enjoyed his Year in Urbanism roundup so much.

If in the race to build better cars we take our eye off the goal of building better cities we will miss a huge opportunity to improve not only emissions, but many aspects of society, life and health.

Don’t forget to grab your free copy of our eBook, Emit This.

Lindsay Wilson

I founded Shrink That Footprint in November 2012, after a long period of research. For many years I have calculated, studied and worked with carbon footprints, and Shrink That Footprint is that interest come to life.

I have an Economics degree from UCL, have previously worked as an energy efficiency analyst at BNEF and continue to work as a strategy consultant at Maneas. I have consulted to numerous clients in energy and finance, as well as the World Economic Forum.

When I’m not crunching carbon footprints you’ll often find me helping my two year old son tend to the tomatoes, salad and peppers growing in our upcycled greenhouse.